Group K3 share their insight into the competitive advantages that have allowed Toys ‘R’ Us to dominate the US toy market and the national differences which obstructed their expansion overseas.

Research has shown that Toys ‘R’ Us (TRU) has strong FSAs. A number of examples can prove this. Firstly, the company has pursued a push system that allows store managers to adapt stock to local needs as well as monitoring positive and negative sale trends. This leads to a logistical system that is quickly responsive. It was developed in the United States and later introduced in Japan.

Secondly, TRU has a strong relationship with local manufactures and large toys companies in the USA. This contributes to reduce its cost and maintain low price because TRU directly deals with manufactures. TRU is also capable of handling regulatory issues and adapt strategy into foreign markets.

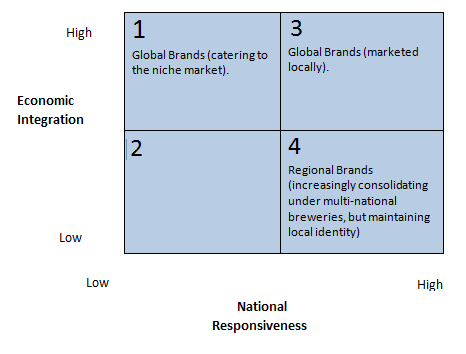

In addition, the company uses superior technology for effectively monitoring its inventories. Finally, TRU has strong connections to the government in both Japan and Germany. The company can thus be located in the below right tier box (quarter 4) of the FSA-CSA Matrix.

Even though TRU was able to overcome some issues faced in some countries, the host countries specific advantages (both Japan and Germany) could be considered weak even that it does not affect the firm’s internationalization and profitability. For example, TRU loses part of its profit because of currency exchange rates (Yen is strong currency when compared to USD). Moreover, the government policy and store size regulations in Japan affect the company operation.

Eventually, the company has succeed in adapting different situations in each country that it enters e.g. Japan but it has failed in Sweden because TRU lacked of understanding both the labour and capital markets.

In terms of positioning in its international activities, by forming a joint venture with McDonalds’s in Japan, TRU has found local partner to overcome barriers, regulations and real estate decisions. The company also has changed the retail format, distribution systems and location strategies to understand local customers. On the other hand, TRU did not form joint ventures in Europe and suffered from lack of adaptation to the European market, including issues to meet local conditions and working relationships.